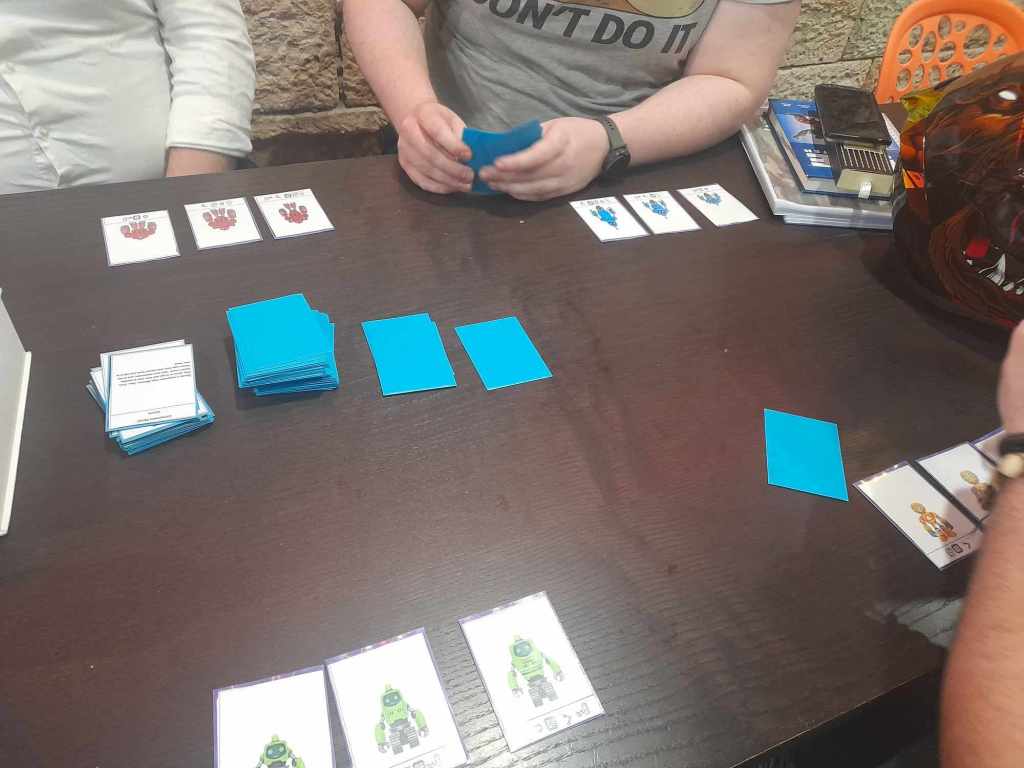

Going into game development, I had heard that playtesting is often a long and complicated process. Having done playtesting now with friends, family and strangers alike, I can now confirm that sentiment for myself.

Obviously, I’m still very new to all this and I have a very green perspective on game development, but here are five things I’ve learnt on the playtesting journey so far.

- Don’t be too precious

Yes, the prototype is your baby and you obviously believe in it enough to make a mock-up for a playtesting session. But draft one is never perfect, never ever. There will be mechanics that are too fiddly, too unbalanced or straight up don’t work in a live playtest. Accept the feedback your playtesters give to you, be it good or bad. While it’s great to hear the positives people have to say about your prototype, it is just as important (perhaps even more important) to hear about what is frustrating players and what they find cumbersome or clunky in its execution. While it might be disheartening to hear in the moment, knowing what to tweak and improve will help lead to a better game in the end.

- Respect other people’s time

Your playtesters are doing you a service by sitting down and working through something that may or may not even function as a full game. One of the first R&D meetings I attended at a local game store, I came with some notes and a hastily sketched out game board for an idea I had been percolating for a while. When prospective playtesters sat down to try my game, they instead got an earful of my ideas and broad strokes about what the game might be and how it might work. When someone asked if we could actually play a version of the game right now I was a bit taken aback and sheepishly told them that no, I wasn’t close to a playable prototype. Looking back on this event, I think I was more than a little disrespectful to the other attendees of the event by bringing something not even close to finished.

To this end, I feel it’s generally good practice to play out your game a few times in solitaire style. Obviously this is easier if your prototype is a solo game or has a solo mode, but it’s not impossible to simulate a multiplayer experience by yourself. Not only will this help you to create a more functional prototype, but it demonstrates consideration for your playtesters, not asking them to do something you haven’t already done yourself.

- Playtest often and with different people

It’s worth getting a diversity of opinions on your game and thus it’s worth engaging with a diversity of players. There’s things you simply won’t have considered in your initial design process that another set of eyes will spot immediately. A broken mechanic, an overturned option that invalidates all the others, a potential improvement that will help with the flow of the game.

It’s also worth mentioning that different players will pursue different strategies, including ones you never thought about or intended to include. They will prioritize certain options, resources or moves, even if they aren’t necessarily optimal, just because they like the shape of the components or the feel of the mechanic itself. Noting what players were drawn to and what they avoided is great feedback, but do remember that what doesn’t work for one player may be a favorite mechanic for another. You can’t satisfy everyone with every option, but you can aim to make a number of playstyles viable.

- Pay attention to end game scores and the balance of different strategies

This point is more mechanical in nature and touches on the aspect of balance within a competitive game. Ideally, in a balanced game, players with similar experience should have similar scores at the end. There can of course be variance between games, explained by random chance, tactical decisions and mistakes made, but if game scores are close until the very end it can be a good indicator of exciting and engrossing play experience.

On the flipside, if a certain option or strategy consistently scores higher than any other, there’s a problem. In an earlier version of one of my games, playtesters that prioritized a certain suite of cards to collect consistently finished the game with a large points lead over their competitors, something I noticed after recording the scores and final boardstates of several playtests.

If there exists an ideal strategy, one that is always disproportionately rewarding regardless of the game state, you have a problem. Players who favor other strategies will feel their choices invalidated and players who like playing optimally will feel bored with consistently choosing the same options over and over.

That’s not to say that there won’t be (or shouldn’t be) a degree of internal imbalance within the final product of your game. Unless a game is perfectly symmetrical, with no chance elements (like chess or go) it’s probably impossible to reach a state of absolute fairness, and that’s OK! There are plenty of games out there in which players choose mechanically inferior options, strategies or characters simply due to aesthetics, overall feel or as a test of skill. It’s fine that some options in your game might be stronger or weaker than others, but you don’t want such a chasm in quality that nobody in their right mind would choose anything other than the most powerful of plays.

- You make the final calls

Shocking as it might be, different people will have differing ideas about what’s best for your game. It’s not uncommon to hear entirely contradictory feedback on what worked and what didn’t, sometimes within the very same playtest. Some people might have enjoyed the random elements of your game, while others might have found them frustrating or that chance was invalidating their decision making. One player might delight in using a “take that” mechanic that weakens an opponent directly, while another will totally abstain from such plays on principle.

Ultimately, it falls to you, the designer, to take these responses and decide on how to progress with your game. You can’t please everyone, some people will just like and dislike certain things. If the game you had in mind isn’t resonating with a certain person or group, maybe it’s just not for them.

A player who’s favorite game is an empire building space epic like Twilight Imperium will have a vastly different perspective from a person who’s favorite game is Uno, and it’s likely that each of them will have vastly different suggestions for where you should be taking your game.

Ultimately, playtesting is an opportunity to stress-test your design in a live environment and receive suggestions. While all suggestions are valuable, some will not be in line with your final vision and that’s OK. Perhaps your game is just not for that particular audience.

A final note

Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Even if you think your game might be the best, most exciting and universally enjoyable experience the world has ever seen, you should not neglect to playtest other people’s games. It’s not only fair to them, especially if they are playtesting your game, but it opens up a wonderful opportunity for inspiration and development.

When playtesting another person’s games, you should conduct yourself in a way you would want a playtester for your prototype to act. Be attentive when they explain the rules and engage as you play the game. Be respectful, honest and forthright with your suggestions, but let them know that they are just that, suggestions.

The game development community is one of the most inclusive and welcoming spaces I’ve ever had the pleasure of engaging with. The respect and humility of the people I’ve engaged with continues to impress me day after day.

And as long as you keep that ethos to heart, I’ll always be willing to sit down and play with you.

Leave a comment